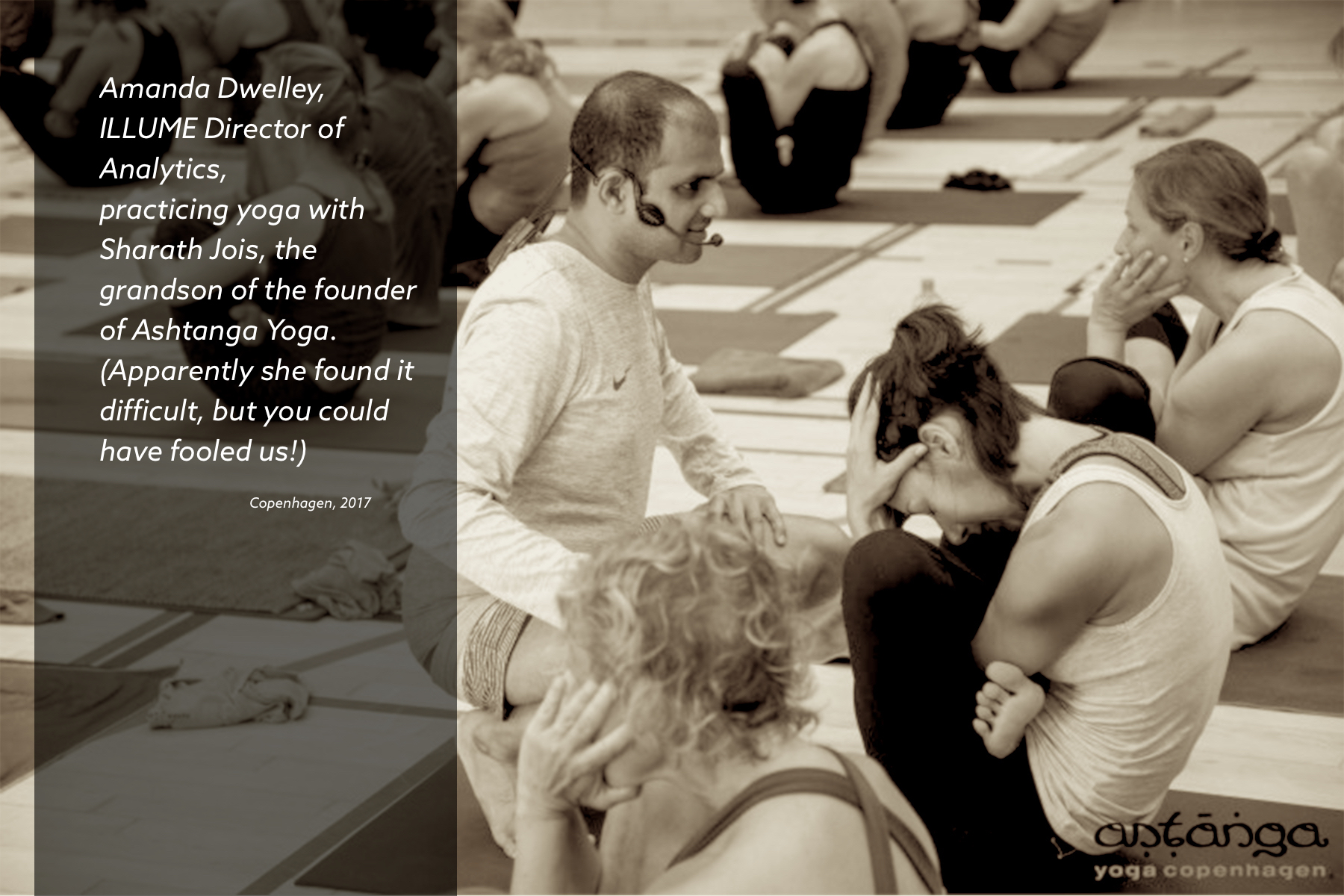

I am in Copenhagen this week for 6 early mornings of 75-minute yoga sessions. You may be wondering, “A transatlantic flight for something you could easily do at home? Why the effort (and carbon footprint)?” The reason that this was so important to me is that I wanted to experience practice with the grandson of the founder of Ashtanga Yoga, who is the current upholder of the Ashtanga Yoga tradition and lineage. Ashtanga is a sequence of postures, movements, and breaths that are highly prescribed. During Ashtanga, every single movement happens on a prescribed breath and every breath is counted. The sequence is ostensibly unchanged from its original teacher. Today, Sharath Jois, grandson of Sri K Pattabhi Jois, teaches the sequence to thousands of students a year, from his packed shala in Mysore, India. He also leads a series of one-week workshops abroad each summer. Students flock to him from around the world to be schooled in what is considered to be a very pure, original form of Ashtanga. So much of what we do in the West has been shifted and adapted and changed from the traditional forms. I was looking forward to the amazing experience of seamlessly slipping into the sequences, movements, timing, and breath counts I am so familiar with, in synch with practitioners from around the world.

SO WRONG! Oh, man did I struggle the first day! The counts were all short where I wanted them to be long (where’s the stretching?) and long when I wanted them to be short (torture!). What struck me (besides the excruciating pain of course) is what an example of flawed translation this was. Even though I thought I had been practicing an exact copy of true Ashtanga Yoga- carefully replicating every breath and movement, somehow, somewhere, there was a mismatch in translation! This strikes me as incredibly relevant to our work in energy efficiency.

Much of our work centers around being fastidious collectors of information, accurate translators of information, and finally ethical interpreters of information. As we are out in the field, listening to customers and clients- we must be vigilant against mismatches in translation, as I experienced in my yoga practice. I got some sore core muscle out if it, but the ramifications could be more serious in our research context.

My colleague Dr. Liz Kelley, ILLUME’s Director of Ethnographic Research brings an incredible depth of knowledge to this particular area. Prior to joining ILLUME Liz’s academic research focused on translation in cross-cultural contexts. Here Liz chimes in: Translation is often discussed in terms of equivalencies, as a matter of finding the approximate (or even exact) substitution in one language for the word in another. But as anyone who speaks more than one language knows, there is often no exact equivalent, even for the most basic and concrete of concepts. Take Google translate, for example. This is a reliable resource for many looking to find a quick translation to a word or a phrase. But the limits of translation are highlighted by parodies produced by Google Translate Sings. The artist takes song lyrics and runs them through a variety of different language pairs (English to Korean; Korean to Japanese; Japanese to Uzbek: Uzbek to Spanish; Spanish to English for example). She then performs the resulting songs. In this clip, she sings “Let it Go” from Disney’s Frozen. Is the translation of “let it go” “Give up”? While semantically, yes—in many cases, “give up” and “let go” would be synonymous-but in the case of this song, the meaning is in fact, quite the opposite. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bVAoVlFYf0

The phenomenon of translation and evolution exists in nearly all fields – historians and comp lit majors, please chime in! Here is some additional context from Liz: In the West, translations have conventionally been conceived of in terms of fidelity (a “faithful” translation) or in terms of what might be ‘lost’ in the translation. In this context, a translation that adheres closely to the original is seen as more ‘faithful’ than one that strays. But this introduces a question of interpretation – one could produce a translation that is ‘literally’ quite close to the original, quite faithful, but figuratively, in terms of impact or effect, quite far. Translation, as an endeavor, is frequently framed as caught between a rock and a hard place—between being too literal and losing the artistry of the original, or straying from the literal meaning, but guarding the sentiment.

Good researchers understand that their job extends beyond analysis and stretches into translation. We must communicate our research if we want it to have an impact. Therefore, we are, storytellers. There are two main parts of a researchers “story”. One is the observable, objective components– a factual representation of what happened. This might be what a camera or video would record. The second is the meaning and intent – the point of the story; what it is meant to communicate. As researchers and evaluators, we are often at risk of passing along one without the other. In some cases, we may pass along “just the facts” but miss the point or intent. For example, how many of us have endured dry, endless PowerPoint presentations– full of facts and figures– but left the room wondering, “What the heck was that even ABOUT?”. Conversely, we can err in the other direction by passing along lots of meaning and intent, but without substantiating it with the underlying or original information. This may come in a form of an executive summary, for example, heavy on extensive recommendations but seemingly unconnected to the research questions, activities, or findings. Both are a failure in translation.

Here, Liz brought up an everyday example from Clifford Geertz’ “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretative Theory of Culture”: Geertz discusses the difference between a “twitch” and “wink.” He notes that from the perspective of a camera (an ‘objective’ perspective, that is), the two physical movements are indistinguishable. However, in terms of their social meaning, the two gestures indicate vastly different things. Or more to the point, the wink indicates something whereas the twitch does not. Ethnographic description (thick description) for Geertz is not like the objective image of a camera precisely because it includes this social meaning – the wink expresses some kind of shared interest or solidarity; it serves to create or solidify a relationship between individual; the twitch does not carry this social significance.

As humans, we are such natural “interpreters” of these subtle differences that it can actually blind us to the “the facts”. We are SO convinced that we understand the intent, that our mind generates false facts to shore up our conviction. This is a huge problem in eye-witness accounts of crimes, for example. Anyone who has run a focus group before knows that when seven people watch the same focus group, there are potentially seven different recollections of “just the facts”. Often, interestingly enough, despite some facts being off, there is generally a consensus on the overall takeaways. As researchers, and purveyor of the facts, we must balance our own human limitations by relying on rigorous procedures that create systematic checks and balances. The following research suggestions bring together “the facts” and the “meaning” to create a whole picture.

First, research that allows you to directly observe or listen to people can be incredibly insightful – whether it is through in-person discussions, focus groups, in-store observations, home energy audit ride-alongs, or sitting down with someone at their computer or phone to actually watch how they work through a process like online research or an online application (…and the list goes on…let’s be creative!). Within these, “in situ” observation like in-home/in-store research or usability testing provide even more direct experience; even with in-person discussions or focus groups, the participants are still interpreting/translating their own actions and opinions! Similarly, survey research, while attractive for that sense of quantifiable truth, reflects many layers of translation by the time you read them in a report: The participant interpreting the question; the participants’ cultural context in responding (e.g., bias toward positive ratings); the researchers’ interpretation of their responses; our framing of quantitative information in a report; our prioritization of some findings as more important than others. Sometimes it is valuable to do small-scale ethnographic research before writing a large-scale survey to simply get the language right.

Second, it is incredibly valuable for multiple people to observe or listen to the research – to hear feedback first-hand. The act of synthesizing requires interpretation of the facts as well as countless judgments about what’s important; for example, even when you have video there are decisions to be made about what snippets or quotes to pull. Having multiple observers helps you catch all of the important pieces, not only because collective recall improves, but because everyone – researchers and clients – inevitably have a slightly different perspective on the research objectives. Sometimes it feels inefficient to pull someone else into a meeting, however, each additional listener increases your chances of retaining and upholding the factual or objective part of the story, and bringing more context to the interpretation. Both of these are essential for translating project objectives and context all the way through to fieldwork, analysis and developing recommendations.

Third, though as professional researchers we may pride ourselves on the analysis process – interpreting, synthesizing, reporting and visualizing – everything we do has passed through some frame or perspective, no matter how objective we are trained to be. Thus I think there is tremendous value in providing opportunities for users of our research – program planners, managers, marketers, customer outreach, etc. – to experience the raw data first-hand, even in an edited format. It’s not reasonable for everyone to listen or watch every action, so (a) focus groups (online or in-person), though limited in some ways (this could be a separate post…) provide an easy way to do this, as do (b) video recordings or clips of online, in-person or in-situ interactions, or (c) direct transcription of discussions or activities.

Many of this blog’s readers, and ILLUME’s staff and clients – the social scientists, cognitive scientists, psychologists, linguists, historians, literary scholars and political scientists among us – are well aware of the subtleties of translation and interpretation. For me, I hope that thinking about our research as covering spanning to bring renewed care and consideration for (1) the language we use in data collection, (2) the context of the respondent and the interviewer in giving meaning to an interaction, and (3) how we share findings and ideas.

(ps. *Tying up the yoga thread for those who can name more yoga styles than professional sports stars…I really recommend Breath of the Gods on Netflix, which walks through the lineage of the practice.)