My mother-in-law owned a small flower and gift shop in New Hampshire. She opened her doors in a historic building in the late 1970s, and she devoted her time and creative energy to nurturing the business and caring for her customers for more than 20 years. She did it all—from negotiating with her wholesalers to dealing with building maintenance to invoicing and payroll on Saturdays.

As a small business owner, my mother-in-law was a member of a sector that makes up a significant portion of our economy and energy footprint. There are 30M small businesses in the U.S., employing 48% of the country’s private workforce and collectively spending $60B a year on energy. SSmall businesses and the people who work there are vital to shaping our energy future.

Recognizing the role of small businesses, utilities have long offered efficiency services in the form of direct installation and lighting programs. In 2016, the Minnesota Commerce Department, through its Conservation Applied Research and Development (CARD) grant program, funded research projects to better understand the opportunities for small businesses to save energy beyond lighting retrofits. One of these projects, led by ILLUME in partnership with Slipstream, quantified the opportunities for energy savings through low-cost or no-cost changes to energy consumption behaviors.

When I think about my mother-in-law’s business now, I wonder how high her utility bills were. Between the refrigeration for the flowers, the lighting, and the drafty building—they must have been enormous. While she owned her building, she, like many small businesses, faced additional hurdles to reducing energy consumption—limited capital for large investments, little staff time, and concerns about disruptions and adverse effects on her business.

Low-cost behavior-change approaches can lower barriers to participation. However, to work, they need to be based on behavior change best practices and, more importantly, in maintaining and improving business processes. For a florist, this would mean adequate refrigeration for flower quality while maintaining comfort for customers shopping for longer periods of time, like when planning flower arrangements for a wedding. Other businesses will have different concerns, from food safety to lighting to office comfort.

For our work in Minnesota, we completed extensive data collection and analytics to quantify the potential for savings and then interpreted those opportunities within a framework of behavior change strategies to suggest potential program approaches. We found substantial opportunities for small businesses to save energy.

To estimate potential energy and bill savings from behavior change, our research team surveyed 1,450 small businesses (those with fewer than 100 employees) in Minnesota with a sample stratified by the number of employees, location, and business type. We gathered information on business practices, building characteristics, and decision-making authority. We also asked businesses about their current energy use practices related to 15 end uses, including lighting, HVAC, plug loads, refrigeration, and kitchen exhaust fans.

We combined the survey data with industry and academic research, and a third-party dataset of all small businesses in Minnesota, to develop building energy model inputs to narrow the initial list of 15 behavior changes to the 10 changes with the greatest savings potential using the DOE2.2 building modeling engine. In all, the team ran 5,600 simulations to model energy use for 6 business segments, 3 building types, 2 building sizes, 2 HVAC types, 2 heating fuels, and 3 climate zones. These models estimated building energy use with the implementation of 10 energy-saving approaches plus a baseline condition.

Final savings estimates represent achievable savings. We incorporated adjustments for current practices, decision-making authority, one-time versus repeated actions, and changes that can be accomplished through a sensor or control.

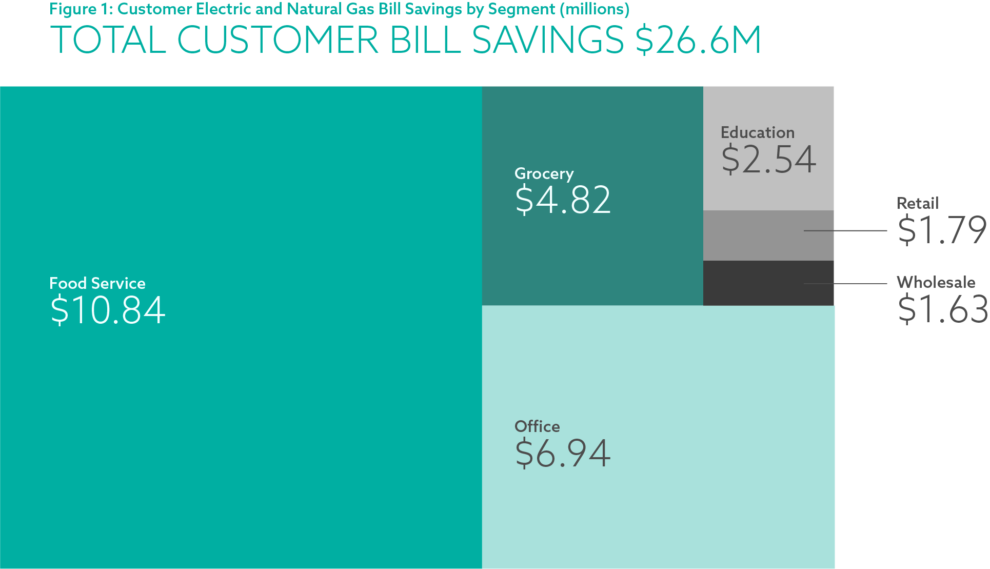

For the 10 behavioral approaches and the 6 business segments, we estimated total achievable savings of 245.7 million kWH and 7.8 million therms—enough energy to power nearly 23,000 Minnesota homes for a year and to heat nearly 12,600 Minnesota homes in the winter. The team calculated a total annual benefit of $28.6M in customer bill savings for small businesses statewide. The results show that businesses in all six segments have opportunities to save energy, with the largest opportunities in the food service and office segments and the largest end-use opportunities in thermostats, kitchen exhaust fans, and refrigeration.

These estimates account for many of the limiting factors of small businesses; however, poor communication or the wrong delivery approach can also impede adoption. Drawing on the literature on behavior change strategies, we highlight approaches to integrate energy-saving behaviors into business practices, existing programs, or activities that also foster teamwork or friendly competition. For example, a small retail business, like my mother-in-law’s, might find it helpful to implement a comprehensive open/close checklist that includes what to do with energy-using equipment as well as door locks, cash registers, merchandise, etc. Food service establishments that are members of a franchise can use competitions to improve processes, encourage energy conservation, and boost morale.

We went beyond looking at just potential. Insight is only as good as it can be easily implemented to make positive change. Through the practical application of our analysis, we showed Minnesota utilities the best ways to encourage behavior change so that it costs less for other flower and gift shops to keep the lights on.

Small Business Profile, U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy, accessed January 8, 2019, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/All_States.pdf

Small Businesses: An Overview of Energy Use and Energy Efficiency Opportunities, ENERGY STAR, accessed January 5, 2019, https://www.energystar.gov/sites/default/files/buildings/tools/SPP%20Sales%20Flyer%20for%20Small%20Business.pdf.